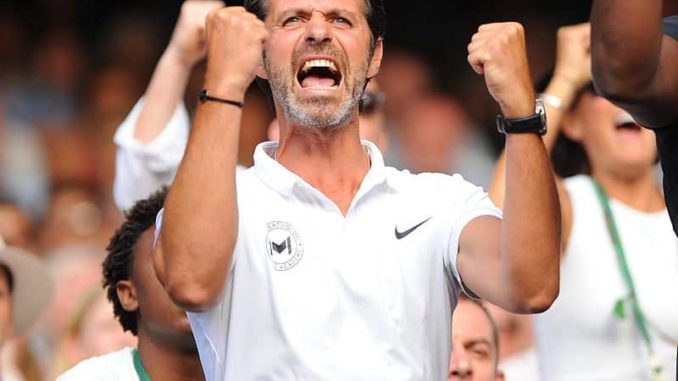

We take a look at the story of Patrick Mouratoglou; from promising young tennis player to world-renowned coach and founder of the Mouratoglou Tennis Academy in France, the man who talent-spotted Stefanos Tsitsipas and relaunched Serena Williams’s career has come a long way to make an impact on the world of tennis.

You may know Patrick Mouratoglou as the coach of the 23 grand slam winner Serena Williams. You may know him as the man who built the Sophia-Antipolis Mouratoglou Tennis Academy, where top players like Stefanos Tsitsipas and Aravane Rezaï have come to improve their game.

However, success stories are only as good as the obstacles they present the hero with, and Patrick Mouratoglou had to overcome a couple.

[the_ad id=”25431″]

Troubled beginnings

Born to Pâris Mouratoglou, a successful entrepreneur involved in renewable energies who founded what is now called EDF Renewables, Patrick was a timid, fragile kid who lacked communication skills.

Often over-worried to the point of being sick during school, he struggled to find a sense of confidence from a young age.

Tennis brought relief and a sense of belonging to his anxious mind. When he was about four, his family went on vacation, like they usually did, to meet with family friends.

These friends had kids the same age, and to make the afternoon a little quieter, the adults gave the little ones tennis rackets – it was love at first sight for Patrick.

A Tennis Love Story

“The tennis court was the one place where I felt strong. Growing up, if you lack self-confidence, and you manage to find a place where you feel that way, it’s magical. So I spent my whole Saturdays and Sundays there. The opponents came and went, but I didn’t want to leave.”

Asked what made the sport so compelling to him, he gives a straightforward answer: “everything.”

“The sound of the ball hitting the racket, the timing, the running around on the court. […] I find it beautiful.”

Also Read:

The obsession had begun, and it would never stop. Far from a flaw, he considers it a necessary condition for greatness. He now trains young players with high potential, and if there’s one thing that can make him doubt their ability to become a champion, this is it: the lack of obsession.

“If a player tells me ‘I’m not watching tennis when I get home – I’ve been doing it all day!’, that worries me.

“It makes me think perhaps they’re not cut out for it. […] Roger watches tennis all the time, and he’s been in it for 38 years! And you can bet that Serena watches old matches on YouTube every night. She’s watching herself, she’s watching men’s matches – she’s always trying to learn.”

Like many others, including Toni Nadal, Mouratoglou favors mental fortitude over physical prowess. And unlike the body, the mind is a tricky thing to read, especially early on. Multitudes of young players come and spend a short period of time training at the Mouratoglou Academy, and they all bring their A-game.

At first glance, it would seem that there are hundreds of potential future Rogers and future Serenas.

But Patrick has been in the business too long to be fooled:

“Coaches come to me after a week or so and say ‘boy, this player is on it.’ I always reply ‘Of course he’s on it. He’s been here a week. Give it a year.’”

In other words, he knows that to make it, you have to be on it for more than 300 days a year, rain or shine.

Broken Ambitions

Mouratoglou himself had a few years to test his love for the game. At 11, he was talent-spotted by the Ile-de-France Tennis League (where he played). A promising boy, the official recognition confirmed the likely scenario: he was to become a professional tennis player.

However, in 1985, about to enter his junior year in high school, he asked his parents to be enrolled in a special program for young athletes, divided between classes and training.

[the_ad id=”14063″]

There is a step between amateur and professional tennis, and this was the moment to take it.

“If I wanted to make anything happen for myself, I needed to train twice a day, I needed to travel, I needed to hire a coach.”

His parents refused.

Mouratoglou put his racket in the broom cupboard and didn’t pick it up again for seven years.

“I give everything 100%. It’s the only way I know. I’ve never been able to do otherwise, and I never will – in a way, it’s for the best.”

It made no sense to the passionate young man to continue playing for sport, so he simply stopped.

“Either I play to be the best, or I don’t play at all.”

Also Read:

Seven years later, Mouratoglou had made a career for himself, and he was doing well. But tennis still haunted him.

During his lunch breaks, he drove to the nearest club just to look at the courts. Sitting alone in silence, he imagined rallies, tie-breaks and championship points.

Finally deciding he had been away from the sport long enough, he hired a personal coach.

In his own words, “it was utterly ridiculous, it made no sense at all.”

A self-described “lunatic”, he spent every waking moment outside of work practicing the sport and getting his body in shape, running laps in Parisian municipal parks at night, by 0°C – towards no apparent goal (it was too late for slams).

The Tennis Academy: an Ambitious Project

The goal took shape in 1996, when Mouratoglou was 26.

His broken ambitions fueled his desire to give others what he didn’t get. He wanted to know “what happens at the top”, and to help others reach it.

With his personal trainer, another tennis fanatic, they embarked on the tennis academy project – first a couple of courts rented out from a local club, and a handful of 30-year-old players trying to get in shape. The business was sound enough, and very cost-effective, but Mouratoglou dreamt of bigger things.

“I realized we were never going to train top players like that. We needed a name.”

The name came with Bob Brett, the famous Australian tennis coach (to players like Becker and Ivanisevic), who agreed to lend his trademark to the newborn school.

He was one of the first believers in the Mouratoglou Academy – at a time when they were few and far between.

Mouratoglou Academy Coaching Method & Results

Mouratoglou’s coaching is famously tailor-made.

He adapts to the players as much as they listen to him.

When he came into the industry, back in 1996, the model was the famous Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy in Florida. Mouratoglou compares Bollettieri’s methods to commando training: “Either you don’t make it, or you do. If you do, then you’re a superhero, because you’ve survived very harsh things.”

Unhappy with the high-risk approach and high number of casualties of this method, and unconvinced by the standardization of the Bollettieri school, Mouratoglou came up with his own technique, the polar opposite of one-size-fits-all.

“For me, players are like diamonds. I have so much admiration and respect for them; I just can’t let them go to waste.”

Famously comparing his players to F1 cars, he adds: “You can’t treat them like mass-produced vehicles.”

In the beginning, very few were willing to buy tailor-made coaching. Bob Brett was one of them, and played no small part in increasing the academy’s notoriety and credibility. But Brett left suddenly in 2002, dealing a considerable blow to the academy.

Mouratoglou comments “at the time, I’m thinking ‘this is the worst investment I have ever made.”

Associating with another top coach meant risking history repeating itself, and changing the name of the academy every five to six years – a poor tactical move.

No choice for Patrick but to use his own surname; however, as a brand, Mouratoglou meant nothing.

Mostly behind the scenes, Patrick was not a coach, and knew very little about the profession. A fast-learner, he quickly became one however, and results started to roll in. Soon, there was no need for a new Bob Brett – Mouratoglou was delivering on his promise.

In 2006, he helped Anastasia Pavlyunchenkova skyrocket from 350th in the world to 25th – earning her the “Best Improved Player” title that year.

The French Aravane Rezaï earned more prize money in a single year coached by Mouratoglou than in the rest of her career.

Marcos Baghdatis, talent-spotted by Mouratoglou in 1998, reached the 2006 Australian Open final, losing in four sets to then number one Roger Federer.

Since then, Tsitsipas, Coco Gauff, and Alexei Popyrin have reflected very well on the Academy.

The Dynamic Duo: Mouratoglou and Serena

Perhaps Patrick Mouratoglou’s single most famous achievement is Serena William’s relaunched career. In 2012, the player began struggling: then-ranked one in the world, she lost to the Frenchwoman Virginie Razzano (111th in the world) in the opening round of Roland Garros – a career first.

Two days after the loss, Serena sought out Mouratoglou, and the two have been working together ever since.

However, Richard Williams, Serena and Venus’s father, had always been the coach. Mouratoglou was a challenge to his authority, and was made to feel it: at Wimbledon, the same year, Serena lost a set to Shvedova: Richard asked Patrick what was going on.

The subtext was clear, but Mouratoglou stuck to his beliefs, and stood up to the reproach.

Chris Evert later commented:

“I think her independence started there for sure. That was the first time she went to a resource outside of the family that her dad didn’t have control over. That goes with the evolution of her being her own person.”

And it worked: Serena won the tournament, and then the US Open, as well as seven grand slams and three Masters, plus the Olympic gold (singles and doubles) after she began working with Mouratoglou.

The only hurdle still left for Serena is the famous Margaret Court record of 24 slams, which she is one win away from matching, and, perhaps more importantly to her, two wins away from topping.

Like with any player, Mouratoglou often struggles coaching Serena. But they see eye-to-eye.

“He gets me” she says.

And it’s not a coincidence: “I developed a certain aptitude for reading people’s minds when I was a kid.” says Mouratoglou.

“I was so shy that I spent most of my time just watching. My weakness turned into a strength – it always works like that.”

Summing up his own character, he adds:

“Yes, I have intuition. But everyone has intuition. I guess the difference is that I trust it.”

And what a story! Keep them coming.

Agree! Well-written and refreshing piece of journalism with a good way of telling a story, as opposed to opinionated and biased what they call “blogs”!